“We don’t see things as they are. We see them as we are.”–Anais Nin

“An illusion in the misleading technical sense that if you take a physical measurement and compare that to your perceptual judgment, there’s a discrepancy.” Duke University neurobiologist Dale Purves – as reported by Diana Steele / Special Contributor to The Dallas Morning News

“One of the deepest problems in cognitive science is that of understanding how people make sense of the vast amount of raw data constantly bombarding them from the environment” [Hofstadter, 1995].

Take a moment to observe the world around you. For example, if you tilt your head, the world doesn’t tilt. If you shut one eye, you don’t immediately lose depth perception. Move around an object: The shape you see changes, yet the object remains stable. Look at some of the illusions on this web site. Even though you may intellectually know that you are being fooled, it does not stop the effect from continuing. This indicates a split between your perception of something and your conception of it. In many cases your higher order cognitive abilities cannot influence your lower order perceptions.

“…Ambiguity is pervasive; but the conscious experience of ambiguity is quite rare.” – Bernard Baar

“The brain puts tremendous effort into making sure that you don’t get illusions.” This wouldn’t be surprising, he says – except for how complex the brain’s synchronization has to be to present a seamless reality.” David Eagleman, Salk Institute for Biological Studies – as reported by Diana Steele / Special Contributor to The Dallas Morning News

There is ambiguity in all forms of perception, but the one that might be of most concern to cognitive practitioners is the ambiguity of language. Languages are subject to the same ambiguity as an optical illusion. Sentences such as “This sentence is false.”, provide the illusion that something real is being said, but closer examination indicates a paradox.

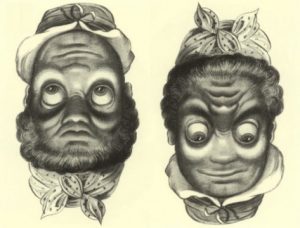

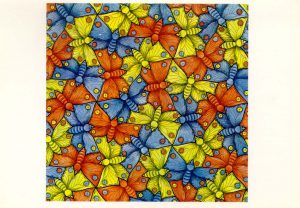

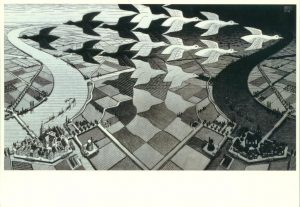

In some cases, illusions take place because the constraints for interpreting an image are ambiguous. Your visual system can interpret the scene in more than one way. Even though the image on your retina remains constant, you never see an odd mixture of the two perceptions – it is always one or the other, although they may perceptually flip back and forth. Normally, this does not happen in the real world, as your visual system has evolved many different ways to resolve ambiguity. Visual perception is essentially an ambiguity-solving process.

In a similar manner, the mind seeks to eliminate ambiguity in all areas. One of the outcomes of this is that the mind ‘chooses’ to believe one interpretation over another. Usually this choice is based upon the unconscious mental contexts that have grown through experience and imagination over time. As Ludwig [1988] put it: “The mind is much less on organ of rationality than of rationalization. Because the individual has to live with himself, his mind tries to legitimize his intentions and behaviors so that he need not feel guilty, so that he can convince himself that his is making the right choice.”

In a similar manner, the mind seeks to eliminate ambiguity in all areas. One of the outcomes of this is that the mind ‘chooses’ to believe one interpretation over another. Usually this choice is based upon the unconscious mental contexts that have grown through experience and imagination over time. As Ludwig [1988] put it: “The mind is much less on organ of rationality than of rationalization. Because the individual has to live with himself, his mind tries to legitimize his intentions and behaviors so that he need not feel guilty, so that he can convince himself that his is making the right choice.”

Or as Gilbert [1993] says “The problem is that when we say a person seeks true information we really mean that the person seeks information that [s/he] considers true. …subjective truth is largely a matter of coherence; statements that complement (rather than contradict) what one already believes are likely to be seen as true.” thus, we might say that the person “deludes” him or herself into believing what s/he perceives, choosing perhaps to see something that is not “real” in the sense of what most of the rest of us perceive.

It seems that delusions are much more commonplace than most people would assume. “A belief is considered a delusion if a person holds to it no matter how bizarre it is and despite all evidence to the contrary.” “…researchers say the delusions of those with psychiatric disorientation are fundamentally no different from, say, a private belief that a color is unlucky or popular beliefs in the existence of flying saucers.” [Goleman, 1989]

Dr. Brendan Maher, a psychologist at Harvard has said, “Many or most people privately hold strange beliefs that could be diagnosed as delusional if brought to the attention of a clinician.” [Goleman, 1989] If this is so, should we believe that such people are psychologically unfit, and if so, what does this say about the ability of humankind to survive? “In 1917…the classification system used by the American Psychiatric Association included only 59 forms of mental complaint. By 1952 … there were 106. By 1989… 292.” The latest version 1994 of the manual, which is employed by mental- health professionals, lists 396 possible diagnostic codes. This proliferation of labels is causing some dismay. Indeed, some critics wonder if the multiplication of mental disorders has gone too far, with the realm of the abnormal encroaching on areas that were once the province of individual choice, habit, eccentricity or lifestyle.” “As one psychologists says, ‘It’s a very political process.” [Goode, 1992]

Webster defines hallucinations as false illusions. But illusions are false perceptions. Does this sound like double talk? Hallucinations are false perceptions, which are false. And since truth is in the eye of the beholder, is the perception false or simply not verified by others? “Those who hear voices are usually considered psychotic or saintly” [McCarthy, 1993] Would Jesus be suffering from delusions of grandeur or perhaps hallucinating the presence of God? How do we separate the common psychotic from the saint, and who is justified in making that decision?

In the course of her research, psychotherapist Myrtle Heery indicates that otherwise ordinary people may sometimes hear voices, too. Heery emphasizes that her subjects ‘are functioning members of the community’ [emphasis ours] [McCarthy, 1993].

The lowest perception occurs, of course with the reception of raw sensory information through the various sense organs, described as sensations. Out of the many sensations the mind seeks to find an orderly process by which to make sense of the world. Perceptions, however, may be influenced by belief, goals, and external context. This implies that there is a top-down process along with the bottom-up process of the senses. In order for raw data to be shaped into a coherent whole, it must go through a process of filtering and organization, yielding a structured representation that can be used by the mind for any number of purposes. The result of this process is that everyone’s mental context is different and we may all see things differently through our individual lens.

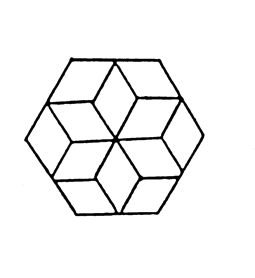

In Perspective & Personality, we present an illusion that is reported to have eight different perspectives, although I admit to finding only six. Partially, this may be because I do not have an independent form in mind to construct from. For as Albert Einstein [1949] pointed out ‘It seems that the human mind has first to construct forms independently before we can find them in things …knowledge cannot spring from experience alone, but only from a comparison of the inventions of the intellect with observed facts.’

In Perspective & Personality, we present an illusion that is reported to have eight different perspectives, although I admit to finding only six. Partially, this may be because I do not have an independent form in mind to construct from. For as Albert Einstein [1949] pointed out ‘It seems that the human mind has first to construct forms independently before we can find them in things …knowledge cannot spring from experience alone, but only from a comparison of the inventions of the intellect with observed facts.’

Although we see things differently, everyone finally can see the illusion if a construct is supplied. It may take a while, but finally all see the illusion. Some people just do not see anything, but with a little help in focusing the construct they too can see the illusion.

Illusions can be considered distortions in perception. They represent differences in the appearance of a measurable aspect of the world such as size, distance, and shape. Sometimes there are hidden things in a picture. There may be another picture or a design inside the original picture. We get used to how things are supposed to be, and sometimes our brains get the clues all wrong.

Our brains put images together because they have learned to expect things, and sometimes the data might get a little confused. We may see an illusion because we know what we are supposed to see, even though part of a picture or design may not be completely there. The basis of using illusions within this site is to project how we perceive things. If our brain and eyes did not function as they do, we would not see illusions as we do.

Some optical illusions are just taken for granted, such as movies or television. They just show you a continuous flow of still pictures, one right after the other. Your eyes along with your brain fill in all of the empty spots. Your brain has learned to expect movement. As a result, your brain can fill in all of the missing pieces and the picture appears to be actually moving, even though it really isn’t!

When we say that an illusion is an error in perception – what do we mean? Who is to say that what we see is not the correct image and what everyone else sees is the error. Aristotle probably said it best – Consensus omnium – What everyone believes is true. While everyone is difficult to measure, there is a common sense of what is true, and there is some merit in this common sense even though it too is subject of illusive interpretation and error as described in the article on Culture.

Finally, the illusions have a relationship to paradigm shifts. The well-known illusion of the old/young woman can represent the difficulties of shifting paradigms. When one perspective is held tightly – for example the old woman – it is very hard to see the other perspective. In fact, some people will think you are lying about there being another perspective. When they finally see the other perspective – usually after someone has a) indicated what the other perspective was, thereby giving the person and independent form to look for, and/or b) giving specific hints about what a line represents, the person is then able to ‘see’ the perspective for the first time. This is like an epiphany, but, depending on the difficulty of the illusion, sometimes hard to hold. After practice, one can see both perspectives at will. However, note that they cannot be seen at the same time. What happens in a paradigm shift is that multiple changes in perspective exist and the person rigidly holding an old perspective cannot see, hear, smell, taste or feel the new perspective. When there is finally breakthrough, they will have difficulty holding onto the new image, thought, concept, idea. Finally, they will be able to see both perspectives at will.

Finally, the illusions have a relationship to paradigm shifts. The well-known illusion of the old/young woman can represent the difficulties of shifting paradigms. When one perspective is held tightly – for example the old woman – it is very hard to see the other perspective. In fact, some people will think you are lying about there being another perspective. When they finally see the other perspective – usually after someone has a) indicated what the other perspective was, thereby giving the person and independent form to look for, and/or b) giving specific hints about what a line represents, the person is then able to ‘see’ the perspective for the first time. This is like an epiphany, but, depending on the difficulty of the illusion, sometimes hard to hold. After practice, one can see both perspectives at will. However, note that they cannot be seen at the same time. What happens in a paradigm shift is that multiple changes in perspective exist and the person rigidly holding an old perspective cannot see, hear, smell, taste or feel the new perspective. When there is finally breakthrough, they will have difficulty holding onto the new image, thought, concept, idea. Finally, they will be able to see both perspectives at will.

Needless to say, the admonition from cognitive behaviorist Ron Farkas – “Don’t believe everything you think! – can serve you well both while examining both the articles and the illusions. The ability to see things as they are is what we seek. The Buddhists call this enlightenment.

In getting back to the illusions, they are on the site are for two purposes: first, they are enjoyable, as most people will take the trouble to try to figure out the unique ambiguity of each one. Second, they indicate a major construct of the site: that perhaps was best said by Kant, “Concepts without percepts are empty; percepts without concepts are blind.”