Introduction to Performance Outcome Measurement

Human service managers today are intrigued by outcomes. It is a fad which is given a great deal of “lip service” but very little of anything else. We rationalize that the field is not far enough along to be able to define outcomes. Or we don’t have time, because of day-to-day crises. We want quality, but it is not really important. The real reason is often that we know we are not as effective as we would like to be, so we don’t want to be held accountable. This is when we so often want to consider outcomes without defining a standard. We are not clear about what we intend. We say things like: “I want to do what’s best for kids.” What a wonderful thought. Shouldn’t we all be this caring? However, people who use this kind of mantra often differ in “what is best for kids”. Until we decide what is best for kids, we have no means of measuring outcomes or of making decisions about management performance. Quality is performance consequences equal to preferred expectations; all else is rhetoric. But what is the preferred expectation, and whose expectations should we meet?

For instance in a videotape titled Lasting Feelings, where the clinician Leslie Cameron Bandler was working with a women who was pathologically jealous, you needed to question the purpose of the intervention. If the intention was simply to “fix” the client’s jealousy, then the clinician could have taken the client through a desensitization process. A clinician who did this would probably not even be aware of the default outcome chosen: “I want the client to be indifferent to seeing her husband interact with other women”. Both the clinician and client might in fact have been satisfied with this result and might have regarded the work as a major success. But desensitization would not have enriched the client’s relationship and self-esteem in the way Bandler was able to do by working from the basis of a much richer and more “ecological” outcome.

“The right act can readily be known once the greatest good has been determined, for it becomes simply that act which enhances the realization of the greatest good, and the immoral act is that mode of behavior which is a deterrent to its realization” [Sahakian & Sahakian, 1993]. Unfortunately, in human services we have many opinions about what the greatest good is; yet we rarely discuss our differences. We employ staff based on the quality of the credentials they hold and generally ignore whether or not they believe that “what’s best for kids” is the same as what we believe.

Most human service organizations regularly monitor and report on how much money is received, how many staff there are, and what kind of programs they provide. They can tell how many individuals participate in the programs, how many hours are spent serving them, and how many brochures or classes or counseling sessions are produced. In other words, they document program inputs, activities, and outputs.

- Inputs include resources dedicated to, or consumed by, the program. Examples are money, staff and staff time, volunteers and volunteer time, facilities, equipment, and supplies. For instance, inputs for a parent education class include the hours of staff time spent designing and delivering the program. Inputs also include constraints on the program, such as laws, regulations, and requirements for receipt of funding.

- Activities are what the program does with the inputs to fulfill its mission. Activities include the strategies, techniques, and types of tactical interventions that comprise the program’s service methodology. For instance, sheltering and feeding homeless families are program activities, as are training and counseling homeless adults to help them prepare for and find jobs.

- Outputs are the direct products of program activities and usually are measured in terms of the volume of work accomplished – for example, the numbers of classes taught, counseling sessions conducted, educational materials distributed, and participants served. Outputs have little inherent value in themselves. They are important because they are intended to lead to a desired benefit for participants or target populations.

If given enough resources, managers can control output levels. In a parent education class, for example, the number of classes held and the number of parents served are outputs. With enough staff and supplies, the program could double its output of classes and participants.

However, if you do not consistently track what happens to participants after they receive your services, you cannot know whether your services have had any impact, either positive or negative. You cannot report, for example, that fifty-five [55%] percent of your participants used more appropriate approaches to conflict management after your youth development program conducted sessions on that skill, or that your public awareness program was followed by a twenty [20%] percent increase in the number of low-income parents getting their children immunized. In other words, you do not have much information on your program’s outcomes.

Outcomes are benefits or changes for individuals or populations during or after participating in program activities. They are influenced by a program’s outputs. Outcomes may relate to behavior, skills, knowledge, attitudes, values, condition, or other attributes. They are what participants know, think, or can do; or how they behave; or what their condition is, that is different following the program.

Outcomes for disruptive behavior are clearly measurable – school behavior incidents, detention, suspension and expulsion is up/down 20% over the past three years. For some managers, the goal of reducing disruptive behavior is accomplished through fear, medication, or incarceration. When closely examined, we may find that those who refuse to comply are no longer in the school because they have been “referred” to a mental health agency that has placed them in a psychiatric hospital, partial hospital or residential program. Or those that “respond favorably to medication” [e.g., meet the ‘dead man’ test – which means the more they act like a dead man, the better they are] are in school and no longer act out. Is this what is “best for kids”?

While it is nice that we have begun to realize that we cannot simply collect custodial data which tracks process and not outcome; outcome data is useless unless we have a clear understanding of our mission, purpose, greatest good or summon bonum. Not only does such a discussion help to assure that the greatest good is defined, but it provides a basis for understanding the limitations or constraints upon the process in reaching the outcome. Ending “unemployment” is easy if slavery is acceptable. But is full employment really the goal; or more accurately, is full employment the only dimension of the goal? Might ‘self sufficiency’ be a better articulation? Could we then give everyone a lot of money and make them self-sufficient?

Performance managers cannot avoid a discussion and consensus on life’s greatest good. ‘What’s good for kids’ must be defined in detail if we are to in fact provide it. Further, ‘what’s good for kid’s’ must be demonstrated and in order to do this, we must discuss how we will know when we have gotten there. Is ‘what’s good for kids’ simply that they be safe, well fed, clothed and housed appropriately? Or is ‘what’s good for kids’ something more?

As we begin to examine this in detail, we may find that ‘what’s good for some kids’ is not good for all kids. We may find that individual self-determination is more important than a broad standard. We may decide that the overall determination is that ‘what’s good for kids’ is that they and their families have the support and power to determine their own lives.

Whatever we decide, we become aware through a process of collective thinking that “what’s good for kids” is not an easily answered question and that many reasonable people have arrived at different conclusions. The perspective of the individual making the determination unilaterally is a more powerful influence for ‘what’s good for kids’, than any demonstrable results. Yet most human service managers are perfectly willing to allow reasonable, “good” people to provide services without any real understanding of what they believe is ‘good for kids’.

Kids need love, structure, discipline, etc. Just what does this mean? Is discipline a noun or a verb? Are we going to discipline kids or teach them discipline? Performance management requires not just the measurement of outcome, but also the measurement of outcome against a coherent and consistent standard. And the standard is not a benchmark! Benchmark is a term often used by business to determine the goal of the process. In this sense, a benchmark for human services can only be a ‘perfect’ human being – whatever that means. In a zero defect approach to quality, one seeks to provide services to human beings which will enable them to be perfect. To do any less is to accept mediocrity. This does not mean that one must provide services until the person with problems in living becomes perfect; rather, that we provide services with the intention and expectation that the person with problems in living will become perfect.

This is the requirement of high positive expectation. If we expect only that the person with problems in living stop the behaviors that are giving them [or us] difficulty, that is the most that you will attain; and there is severe question that this will be attainable without a higher expectation. Just as “your reach should exceed your grasp”, the expectation must exceed the outcome. Human beings are goal-seeking entities whose goals expand with each attainment. Hope is a pivotal requirement. It has been suggested that hope is etymologically related to hop, and that it started from the notion of ‘jumping to safety’ – one hope’s that they are not “jumping from the frying pan into the fire”. One might suggest that you cannot even make a dangerous jump without at least the hope of survival.

Hope, therefore, is a substantial motivator in the decision to attempt any new or ‘dangerous’ act. If human service workers are not able to provide hope through their own self-fulfilling beliefs that the person with problems in living is capable of becoming; then what hope can exist?

The human service manager must not only assure that a summon bonum is defined and articulated, but that it is believed by the people who are providing the help. There are two ways for a performance manager to find out what staff believe: 1) ask, and 2) measure outcomes. If you ask staff on a regular basis to comment on their approaches or progress, they will answer in terms that certainly will allow for deduction of attitudes which demarcates belief. Staff who talk about clients as though they were commodities are less likely to have clients who meet outcome expectations. Any number of clues will surface [‘s/he can’t’, ‘its too much to expect’, ‘s/he’s difficult’, ‘I can’t control him’, etc.] From these clues decisions can be made about the need for remedial responses.

We would expect that those who don’t believe in the people they serve will attain fewer positive outcomes; but we may be wrong. Performance management is based on learning. All human services are based on a hypothesis, which should be tested. Only as we respond to data can we learn.

Eight key questions have been developed in regard to outcome management. The first seven by Reginald Carter and the eighth by Positive OutcomesTM. They are reported as follows as written in the Positive Outcomes<sup>TM</sup> Training Manual:

- How many clients are you serving?

When does a client become a client? Duplicated or unduplicated count? - Who are they?

Basic demographics such as age, sex, income, disability level, race and ethnicity. - What services do you give them?

Services are intervention strategies. There can be multiple services. You need to determine which client received which service resulting in an outcome. - What does it cost?

This varies. It could be your budget, your program cost need to sort out hidden administrative costs. Most costs are for personnel. - What does it cost per service delivered?

This is the best measure of efficiency. Divide the total cost by the number of services delivered. This measures services delivered whether or not the intervention is a success. - What happens to the client as a result of the service?

This is the expected client outcome. Also the most difficult and important dimension of management. - What does it cost per outcome?

This is the bottom line and measures the program effectiveness. The cost of a successful outcome. Divide the cost by the number of hoped for outcomes.Source: Reginald Carter. The Accountable Agency: Sage Human Services Guide 34, 1983

- What is the return on investment?

This compares the cost of programs and services for a client with the benefit to the community when the client is less in need or no longer dependent on social services.

This questioning material comes from a training program in which the trainers may have decided not to overwhelm the participants with too much information and therefore criticism of what is missing may be somewhat unfair. Nonetheless, there is no indication of standards, zero based defects or of clients defining quality: e.g., outcome expectations. In addition, it is interesting to note that the trainers added the eighth question which suggests that it is not interested in increasing the quality of outcomes, but rather oriented towards convincing funding sources that there is a return on investment and therefore, continued funding. The return on investment is benefit to the community – in short, it is the double focus of human services: protection of society and/or improvement of people’s performance. Are we really talking about ‘what is best for kids’?

Nonetheless, the questions are worth consideration. For example: if we assume that we help all of our clients achieve perfection as defined by their standards and our own, and there is no benefit to the community or the costs exceed the benefit – do we stop what we are doing? What is your life’s greatest good?

Continuing our review of the key questions, you must wonder whether there is not an initial question that needs to be addressed before you determine your share of the market. That question is: ‘What is the universe of people with problems in living of the type you serve?’ How many children with problems in living exist within your potential clientele? If you are defined by geographic area – how many children between proper ages exist at any given moment and, of these, how many have been identified as delinquent, mentally “ill”, dependent or otherwise labeled as having problems with significant parts of living? If the second is delineated as a percentage of the first – 03%, how many of the 03% do you serve?

For example, a county has about 68,000 individual children/ adolescents who are attending either public or private schools. In all probability, the vast majority are between the ages of 3 and 21. If three percent of these individuals were to experience a problem in living which was severe enough to demand services, the potential target population would be about 2,040. If you served 150 of these individuals over a period of a year, you would be serving a little over 7% of the market. However, the question that needs to be addressed concerns the 2,040.

This is important if you want to impact on the social problems, not just individual clients. A social benefit which is not usually mentioned is that if you are able to help clients achieve a level of social competence which is above present functioning, they will impact on other people who could become clients. Thus even though you serve only .5% of the 03% with problems in living, you should be able to have an impact on more than 01.5% over time.

It is also critical to ask the sub-question listed in number one – ‘When does a person become labeled as having problems in living?’. Human services usually operate responsively since there is rarely funding for prevention. However, by becoming clear about the thresholds for official entry into the humans service system, you may be able to identify behavioral difficulties that lead up to this threshold.

Here is where we separate human services from business. Human Service mangers have no need to increase their percentage of the market; they want to reduce the market! If we could reduce the 03% of children who have problems in living, we are, in fact, reducing the need for our services. Critical question – is this your mission?

If this is your mission, the data you accumulate over time may be used to change public policy rather than to justify what you do. What you do may, in fact, be unjustifiable in regard to the greater good. If you are consciously aware that what you are doing can be compared to applying a band aid after the wound is created; but have the capacity to avoid the wound – how do you justify band aids? A real shift in human services would be to enhance the capacity of the community to nurture its children rather than to remedy the mistakes. [You may want to review Regenerating Community by McKnight in this regard.]

However, it is important that you know who are your clients, in number and type. Disability level is another clue to our constant interest in problems rather than solutions. Would we not be better identifying the ability level?

Service description

What services do you give the client and what is the impact of that service is a critical issue in performance management and often difficult to quantify. The description of services is often incoherent. Thus, people who provide living arrangements describe the services as ‘providing living arrangements’ and people who provide partial hospital services describe providing ‘partial hospital services’. Anyone who has visited two or more of these services is well aware that each service entity [residential day, partial hospital hour, or case management contact] has distinctly different characteristics depending upon who is providing it and the external context of where it is provided. Thus, without a specification of the functional behaviors of staff in regard to clients, there is little definition of services. For example: an hour of counseling can be oriented towards any number of different therapies. Further, each person providing the therapy uses their own individualized style – many claim to be eclectic in their approach, meaning “I will do what pleases me at any given time and if forced to justify it I will respond ‘I only want to do what is best for kids’ ”.

As a manager, you have a responsibility to seek standardization of staff performance. This is of course contrary to conventional wisdom in that we expect individualized services. However, the individualization is based upon the goals and preferences of the client and the standardization is focused on the delivery of the service. At the same time, one does not want to standardize the process as in command and control management. A dilemma arises. How do we standardize without controlling process through command and control. We do so through standardization of staff belief systems, and we standardize these belief systems through the angst of a philosophical consensus on summon bonum. We standardize through a ‘theory of change’. “The manner in which the overall intervention is thought to be related to particular outcomes for a particular population is considered a “theory of change” [Lourie, Stroul, & Friedman 1998].

Without a theory of change, we have no assurance that we are ‘doing the right things’ or that we are ‘doing things right’. As performance managers we are constantly on the look out for incoherence by what staff say and how they act. And, we address these exceptions without controlling the aggregate. When a staff person refers to client resistance and/or compliance, we know we have a need to intervene. If you believe that people can hide their real beliefs, read Bernard J. Barr – A Cognitive Theory of Consciousness.

Once a theory of change is articulated that offers interventions to produce the desired outcomes in the designated population, the next challenge that researchers and evaluators have is to determine intervention integrity: that is, if the intervention has been appropriately implemented. Such a determination can be made only if the intervention is operationally defined and described in adequate detail. It is not possible, for example, to determine if interventions are well coordinated, culturally competent, or family-focused unless an adequate description is provided of the practices that constitute adequate coordination, cultural competence, and family focus [Lourie, Stroul, & Friedman, 1998].

It is also essential that the theory of change indicate the types of outcomes that particular interventions are intended to effect. The main challenges in the children’s services is describing the theorized linkages between provider interventions and child-level outcomes, and finding ways to test the accuracy of these theorized linkages. Without a theory of change, it is even difficult to know what questions to ask. Anyone who has spent serious time doing research knows that the most difficult aspect is to decide on the question to ask. Without a proper question, no amount of methodological skill will provide appropriate answers. If the purpose of collecting data is to answer questions to enable continuous quality improvement, we need to be sure as to what questions we are really asking. What is best for kids?

Once interventions are adequately described, regardless of the level or levels of focus, the next task is to assess the adequacy of implementation of the interventions (often called assessing the “fidelity” of the intervention) [Lourie, Stroul, & Friedman, 1998]. If a planned intervention was not carried out because of a shortage of adequately trained staff or insufficient supervision, there is no ability to answer a question posed by the theory of change. Performance managers in the children’s field, not only need to have clearer theories of change and descriptions of intervention, but also must deal with the difficulty in changing individual staff practice at the level of the child and family.

It should be noted that the task of assessing the fidelity of implementation of the intervention becomes increasingly more difficult as the interventions become more complex [Lourie, Stroul, & Friedman, 1998]. Despite the difficulty of assessing the fidelity of interventions, the task is essential and must be done in order to ensure that evaluation results are not the result of inadequate implementation.

Finally, it is essential that the theory be clear about the population to be served. This enables researchers to determine if the intended population, for whom the intervention was developed, is the population that actually has been served. Only if the intervention is affecting the intended population can the appropriateness of the theory of change and intervention be assessed for that particular population [Lourie, Stroul, & Friedman, 1998].

When measuring results of interventions, it is important to look at trends and not just aggregate counts. Continuous quality improvement is a process of always moving towards quality expectations. As we move, we will find that it gets harder for two reasons: first, the quality standards are raised. As we achieve, we expect more, and therefore the bar is raised. Second, we cannot ever reach perfection. As in cutting a line in half, sequentially halving the remainder, yet we never get to nothing. We always have half a line. So too it is with quality. We can get ever closer, but we cannot attain perfection. Perfection is infinite. These concepts that address the issue of ‘the field’ is not advanced enough to define outcome: your responsibility is relative, not absolute. As you set standards and indicators and measure them, you improve the ‘field’s’ conception of appropriate outcomes by identifying trends and trying to explain them, while continuing to improve them.

Cost

Developing costs is another interesting dilemma. There are at least three levels of cost to the delivery of services. First, there is the direct cost which would include the direct service staff and their peripherals [occupancy, travel, etc.]. Second, is the program administration which would include the supervision and direction of the program, and third, is the administrative overhead. Each public relations cost contributes to the cost of the delivery of services. Allocation of each of these costs has considerable leeway, but should be standardized within your own organization. There are often other marginal costs such as the cost of the space in the home or school where we provide services, the cost of natural support volunteers who attend planning and review meetings, etc., but these require more sophisticated cost analysis which may not be important.

It is not clear, however, that these ‘cost per service delivered’ represent the best measure of efficiency. Unless we compare these costs to all other forms of service over time, we may find that we are not inexpensive. More importantly perhaps, if we find we are the lower cost, we may find that we are not inexpensive or efficient but cheap. The difference in the two terms is, of course, connected with the quality of the service, in this case as measured by substantive impact. If we were to spend more money per hour than any other service, but had a quicker and more long lasting impact our program would be expensive, but efficient.

Thus efficiency is connected to effectiveness because what happens as the result of the services, comparison to what happens in competing services, and the substantive nature of the impact are important criteria in determining the actual cost of the service as opposed to the price of the service to the funding source and taxpayers. The impact of a service cannot be construed without elements of substantive impact on quality of life over time. The service may be very helpful in the immediate, but provide no inoculation or immunity to future circumstance. If this is so, we can expect a fair amount of recidivism since life is full of little traumas. Thus, if we feed the client fish we may reduce or eliminate hunger for now; but if we teach him to fish, we may eliminate hunger for good. Without such inoculation can we really call a service efficient?

Return on investment is likewise influenced by the ability of the client to learn a competence that will enable him/her to cope more successfully and appropriately with the problems in living that are sure to occur throughout life. Too often human service managers look at short-term outcomes and ignore long-term outcomes.

Eliza Doolittle in Shaw’s Pygmalion explains that “the difference between a lady and a flower girl is not how she behaves, but how she is treated.”

Performance management requires that we understand the nuances of how we impact people’s lives. It is not how the child behaves, but how we treat the child that is significant. Peter Senge suggests that another of the difficulties in developing appropriate human services can be identified as a “shifting the burden” problem. “Beware of the symptomatic solution”. Solutions that address only the symptom of a problem, not fundamental causes, tend to have short-term benefits at best. In the long term, the problem resurfaces and there is increased pressure for symptomatic response. Meanwhile the capability for fundamental solution can atrophy.” “Insidiously, the shifting the burden structure, if not interrupted, generates forces that are all-too-familiar in contemporary society. These are the dynamics of avoidance, the result of which is increasing dependency, and ultimately addiction” [Senge – 1990].

Performance management requires an understanding of the fundamental causes of the problems in living and these are rarely apparent, nor in the record. The fundamental causes are the thoughts that promote the behaviors that lead to problems in living. Eliminating symptoms does not eliminate the problem, but merely shifts the burden. The point of this is that outcome measures cannot be seen simply as a reduction of problem behavior.

A practical approach to performance outcome measurement

As we indicated earlier, there are certain terms that are used in developing a system of outcome measurements that are significant to the design. Often these terms are used inaccurately and cause confusion. In working with staff to determine what outcome system should be used, it is important that you specify this language and concepts and for that reason, we will reiterate and expand upon our original discussion.

Inputs are resources dedicated to or consumed by, a program in order to achieve program objectives. These would include, for example, staff, volunteers, facilities, equipment, curricula, service delivery technology, and funds.

Inputs also include constraints on the program, such as laws, regulation, and requirements for receipt of funding. A program uses inputs to support activities.

But most importantly the inputs include clients. One of the ideal ways of improving the quality of outcome is to improve the quality of the inputs. If we can identify children as having problems in living who really have few or no problems in living, we are likely to be very effective in meeting an outcome expectation of ‘no problems in living’ – unless paradoxically, of course, our labeling has a negative impact. One of the vital characteristics of a quality system is the ability to define and measure baseline measures of the inputs. Thus a starting point in concern about inputs is a clear definition of the baseline performance of the various clients within certain specified tolerances. As opposed to widget makers, a human services should be seeking the most flawed client inputs possible in terms of performance in living, rather than the best inputs possible. This baseline data is vital to understanding the outcome.

Establishing baseline data is not a trivial thing. To begin with, what is the baseline measuring? Should we be identifying and measuring symptoms? If so, we would probably tend to seek those aspects of a child’s behavior that is disturbing or disruptive to others. Yet this process is one that is fraught with concern. Many children act in disruptive ways for a variety of reasons, only some of which indicate an underlying problem in living. Other children act [meaning both behavior and pretense] perfectly normal, when inside they are churning with despair. What we really are concerned about are a child’s thoughts as represented by beliefs, attitudes and mental contexts.

This will require that people who provide natural supports be sensitized to and attuned to the child’s thoughts – to know how to probe appropriately for the ‘inner logic’. Thus before we can even begin to define baseline performance, we must ascertain what performance we are going to measure.

Activities are what a program does with its inputs – the services it provides – to fulfill its mission. Examples are sheltering the homeless, educating children, or counseling. Program activities result in outputs.

But there are activities and there are activities. Group workers, for example, often play sports with their clients. However, there is a completely different intent to the activity. Most group leaders who play [or teach] sports to a group of kids are seeking to provide recreation [a good time] or increase athletic prowess. Group workers use the activity to create certain life experiences that can then be used to benefit the personal and social performance of the individual. The differences can be hard for the lay person to see [one thing to look for is the handling of a disruptive child. The recreational or athletic focus tends to expel the child for the benefit of the group; the group worker tends to use the group to help the disruptive child].

So the question is not just what is the activity, but what is the intent of the activity. Is the shelter simply to provide shelter? Or is there an intent to ‘screen’ people’s problems in living. Is it a ‘bait’ to bring people to a training or clinical program? What is the purpose of an education program – is it for academic training? Or are child development issues important? And what are you counseling about. Are you advising a child as to how to adapt to the demands of life? Or are you training a child to develop skills to overcome life’s problems?

Without a summon bonum, how do you know?

Outputs are products of a program’s activities and are usually measured in terms of the volume of the work accomplished, such as the number of meals provided, classes taught, brochures distributed or participants served. Another term for outputs is ‘units of service’. Program like to show an increase in ‘units of service’ to demonstrate increased organizational performance. ‘Units of service’ only indicate the amount of activity, although they may demonstrate a level of efficiency [if we can provide more ‘units of service’ at less cost than other organizations]. However, these outputs have little inherent value in themselves. They show only a ‘custodial’ measure and have no impact on the effectiveness of the organization. It is possible that an organization increases its ‘units of service’ each year and lower cost each year and yet not help a single client achieve an enhanced quality of performance in living. There is no underlying notion of measuring the intent of the activity; and, it is the intent and its impact that are important. It is the impact of intent that determines outcomes.

Outcomes are benefits received by participants during or after their involvement with a program. Outcomes may relate to knowledge, skills, attitudes, values, behavior, condition or status. For any particular program there may be ‘levels’ of outcomes, with initial outcomes leading to longer-term outcomes. For example, a youth in a mentoring program may attend school more regularly, which can lead to getting better grades, which can lead to graduation, which can lead to employment, which can lead to self sufficiency, etc. These things can, of course, occur without any intent at all.

Often, the problem of defining outcomes is not one of too few variables, but too many. Where on the scale of outcomes above is the outcome target for the program and is this target the same as the target of the client; and which target should we select as our outcome expectation. Getting our arms around this problem is one that will require discussion and decision.

First, we must recognize that the organization will probably need to operate at two levels: and to understand both individualized outcome expectation and an organizational outcome expectation. Organizations continue to try to meet the “dead man test”. This is a test formulated on the premise that if the people with problems in living would perform like “dead men”, everything would be fine. Since “dead men” do not perform at all, this requires a total elimination of symptoms. Most client do not consider this to have met their own outcome come expectations which are usually concerned with such things as success, happiness, power over their own lives, etc. Just because a child no longer punches other kids, does not mean that s/he now will have friends. This harkens to the ‘shifting the burden’ concerns of Senge.

In fact, the percentage of individual outcome expectations that conflict with the organizational outcome expectations should send a message to the organization that they are out of step with their own definitions of organizational performance. Quality is essentially a measurement against a standard. The problem is whose standard and to what is it applied? TQM says that it is the customer’s standard that counts.

Further, the standards that measure organizational standards must not be standards of performance meaning process, but standards of outcome. Organizational standards of process performance are epitomized by the regulatory standards now in place. They define specifically who is to do and what they shall do, without reference to what is expected as outcome. Developing standards of process duplicates those regulatory standards regarding means. This does not deny that there need to be certain guidelines about means in public organizations. But the construct that Deming, at least, is trying to help us understand is that, within specific constraints, the staff are capable of designing the means, providing they are very, very clear on what ends are expected.

Nonetheless, the staff may design means that are contrary to the philosophical, ethical, moral and legal expectations of the performance manager and the field. There are constraints to means; one does not develop slavery as a response to unemployment. The constraints to process, however, are defined within the established ‘theory of change’. If we theorize that people change only when confronted by fear, comforting behavior would be unacceptable. It is the conceptual philosophy that provides the constraints of process.

It is an inherent failure of the human service endeavor that we focus on problems and not solutions. In this context, it is suggested that in defining your organizational outcome expectations you focus not on the reduction of defect, but on the increment of competence. Competence can best be defined as capacity equal to expectations. Almost everything we do involves either interacting with other persons or inhibiting interactions with other persons. If we fail to follow the often unspoken rules about these interactions, the consequences will be clear: others will judge us to be socially incompetent [Peter, etal 1998].

Social competence has a major impact on the ability to form trust relationships that are fundamental to living. Thus, social competence, and the resultant social affiliation, has both an individual and a collective social impact. Most clients will define their outcome expectations in terms that can be thought of as an aspect of social competence: ‘success’ in relating to others; ‘happiness’ in mutually satisfying and gratifying relationships; ‘power’ to make competent decision about one’s own life. Thus it is likely that organizational outcome expectations and individual client outcome expectations will be better matched if the focus is on competence instead of defect. If the percentage of variance between organizational and individual outcome expectations is of concern to your leadership, this is an area to pursue.

Once the organizational outcomes have been determined, you will want to recognize that individual client outcomes will need to be determined. This is a difficult and time consuming exercise, to a large extent because most of the people you will serve have been trained to not have opinions or operationalize opinions on outcomes in the extreme. Developing individual outcome expectations will require that you ask. Then probe. Then recast your question. Then probe. Then reframe the answer and ask for confirmation. If you cannot determine what the individual client expects to get out of your program, it is unlikely that you can be helpful. You are not to try to shape the clients outcome expectations to match those of the organization. To do so, will only diminish your hope of meeting either outcome.

There is a question – ‘How far can the client deviate from the expectations of the program and still benefit by participation?’. You may determine that your program is not prepared to help the client reach his/her outcome expectations, but you should have sufficient information to make an appropriate referral. It is not the intent of this paper to detail the process of developing client expectation, but only to indicate the two separate levels that you, as the manager, must make compatible.

Measuring outcomes will require additional dimensions.

Outcome indicators are the specific criterion that will be applied to determine whether the outcome expectation has been met. It should be obvious that the criterion of the organization and the criterion of the client may differ, but hopefully they are not incompatible. If you accept the client and expect to meet his/her outcome expectations, you must be prepared to use his/her criterion. It helps if you and the client have made this criterion clear at the beginning.

Indicators describe the criterion in observable, measurable, characteristics or changes that represent achievement of an outcome. The number and percent of program participants who demonstrate organizational criterion is an indicator of how well the program [or client] is doing. As we indicated earlier, however, there may be levels of outcomes. In order to be clear with both client and staff, it is important to sort out the levels of expectation.

Outcome targets are numerical objectives for a program’s level of achievement on its organizational outcomes. After a program has had experiences with measuring outcomes, it can use its findings to set targets for the number and percent of participants expected to achieve desired outcomes in the next reporting period. It can also be used to determine staff performance in regard to comparison of client participation with staff and approximation of target performance. For example, a school may target that 85% of all students [who enter the program or who finish the program] will go on to college. Organizational success or failure is determined by this outcome standard.

Outcome targets are also the specific outcome expectations of an individual client. S/he will need to address the level of competence necessary to believe that the program has successfully met or failed to meet his/her needs. Thus, while a client may determine that competence in academics is a specific goal, s/he may define the outcome target as meeting grade level in all subjects, getting A’s & B’s, or getting accepted to college. Goal attainment scaling is a good method of determining the percentage of achievement that the client has attained.

Benchmarks are performance data that are used for comparative purposes. A program can use its own baseline [present performance] and outcome target as the field, while establishing points that should be met within those two performance points. It may use data from another program as a ‘benchmark’ to be reached within a certain period of time [time cycle].

Time Cycles are the specific amounts of time [duration] projected to meet a specific benchmark or target. If either an organization or a client wants to improve their performance over time, a time cycle should be used to indicate progress. If for example, an organization has a baseline performance of 60% of students who participate go to college and a target of 100%, it may want to set incremental periods of one year to go to 65%, a second year to get to 70%, etc.

Time cycles have various uses. Like budgets, they are usually experimental the first time. However, as we experience the use of a time line, we can often determine how to improve. Without time lines, we often end up with the equivalent of Freudian analysis, which seems to measure success through the length of time allotted.

The other factor of time lines is that human beings tend to gather themselves only when the time line is about to run out. If one seeks the involvement and motivation of a client in a manner of participation that involves energy, a time line may cause it to happen. Note how many students do ‘their best work’ only the night before the paper is due. Setting a time line that demarcates the end of services can equally cause a gathering of effort.

The dimensions of indicators, targets, benchmarks, and cycles must be an explicit part of the outcome expectations that are articulated for organizational or client purposes. It is only with these dimensions that collection; analysis and use of data for continuous quality improvement can be accomplished.

Data collection & Analysis

The process of data collection and analysis demands four categories of managerial involvement:

Rigorous examination of the intentions and beliefs [values & principles] of the policy makers and the development of plausible hypothesis of how these factors influence the activities of the organization. This leads to the development of a philosophical position upon which social policy [mission] is based and includes the articulation and debate of such social policy.

The development of standards. If quality is a comparison, the organization must establish the point of comparison. It is important that in the present worldview, two sets be considered: organizational standards, and organizational standards that ensure the potential of individual standards.

Not only must standards be developed, but they must also be articulated to all concerned parties as the basis for evaluation. Thus they must not only be clear, they must be understood by all of the major managers of the organization. Organizations must not only state explicitly what is intended in terms of outcome, but in complex organizations, must be prioritized along value lines so that when staff make independent decisions regarding individual outcomes, they do so along the parameters of organizational values, not personal ones. Individual performance [actions] must be coherent to the organizational belief system and intentions. This may require not only clarification of terms, but also a negotiation of managerial values, prioritization, orientation, and reinforcement.

These processes are lifetime projects. Just as individuals are always growing and developing, so too must organizations grow and develop. To assume that this will take place, with managers who are concerned with operations and/or technical aspects of the organization, is to expect too much.

Information capability must be in place. The dimensions of the information must be formative, summative and cumulative. In addition, the information must review organizational performance, individual staff performance, and individual client performance, using the term performance to indicate both the activities and the outcome of those activities; means and ends.

“…quality is different in different settings …for different people.” [Lakin, Prouty, & Smith – 1993] Individualized services require individualized quality measures. “Quality is thereby manifested in the achievement of desired outcomes” [Lakin, Prouty & Smith – 1993] [emphasis added]. It is the personalization of services, quality outcome expectations, data collection of formative and summative individual focus, and the responsiveness to the changes in the client’s expectations as achievements are attained that will contribute to the quality organization.

It is the cumulative data of many clients across time that will be the ultimate organizational performance standard. “Our shared goal is to develop processes and concepts useful for reconceptualizing and redesigning services that honor the distinctive contributions of people with disabilities, their family members and friends, service workers, and other community members.” This action learning approach contributes to organizations learning by creating time and space for reflection and creative problem solving” [O’Brian & O’Brian – 1993]. It also helps to set up a learning process in which the learning entity [client or organization] can begin the process of learning over time how to define quality and measure results through experience.

Little value is gained by attempting a measurement with inadequate tools. Without specific data with which to assess discrepancies between the standards and the performance, we are left to speculative opinion and are unable to objectively implement reward, remedial or corrective action to support and reinforce the organizational intent. It is important therefore to recognize that the ability to articulate measurable effective process is not only limited by our ability to articulate measurable and agreed upon objectives, but equally by our inability to collect data upon which to assess performance and outcome. Lacking a sophisticated system for collecting all of the data we need, we are better off measuring only that which we can effectively articulate and measure, rather than try to exaggerate our capacity and create a system that will be distorted by those that it is intended to reinforce.

Facilitation systems must be in place. It is one thing to articulate standards and collect data for measuring them; it is another to use it effectively. Too often day-to -day pressures from the environment cause us to negate that which is available to effectively implement actions that can alter the way we do business. In order for the process to be effective, people within the operational system must feel the impact of the data collection results. Thus when no discrepancy exists between our expectations and outcomes, or when the discrepancy is to the positive side [we have done better than expected] reward responses including praise, recognition, promotion and compensation must be implemented to reinforce these positive behaviors.

On the other hand, if there were an identification of inconsistencies that are not beneficial and indicate an inconsistence in performance, “two behaviors would ideally occur before any corrective action is taken. The first is hypotheses generation, in which managers identify possible explanations of inconsistency” [Pauley, Chobin & Yarbrouch – 1982]. Were there extenuating circumstances: poor expectation, judgements that led to inappropriate standards, data collection disruptions which led to negative discrepancy, etc.? Hypotheses generation is ideally followed by hypothesis confirmation. When the hypotheses are unable to be confirmed, the manager must take remedial action that could include training, increased supervision, or disciplinary action to remedy the situation and get it back on track. Each of these three response actions: reward, remedial and corrective, must take place on a consistent basis if the operational evaluation process is to have an impact on the organization’s functioning.

The design of the data collection and response facilitation is imperative to a learning organization. Too many agencies collect too much data that is neither analyzed nor responded to. The data collected must be reported in such a way that the information contained is readily apparent and there must be common knowledge that the information will cause a response. We have suggested that three levels of response are possible: we can change the manner of providing services to clients in order to improve the likelihood of positive outcome; we can train, retrain or remove staff who do not produce the same levels of outcome as other staff; and we can reorganize our organizational expectations. The last provides for verification of the integrity and efficacy of the organization to both the potential users and funders.

For example, in a program to counsel families on financial management, outputs – what the service produces – include the number of financial planning sessions and the number of families seen. The desired outcomes – the changes sought in participants’ behavior or status – can include their developing and living within a budget, making monthly additions to a savings account, and having increased financial stability.

In another example, outputs of a neighborhood clean-up campaign can be the number of organizing meetings held and the number of weekends dedicated to the clean-up effort. Outcomes – benefits to the target population – might include reduced exposure to safety hazards and increased feelings of neighborhood pride. Exhibit A depicts the relationship between inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes.

Note: Outcomes sometimes are confused with outcome indicators specific items of data that are tracked to measure how well a program is achieving an outcome, and with outcome targets, which are objectives for a program’s level of achievement.

For example, in a youth development program that creates internship opportunities for high school youth, an outcome might be that participants develop expanded views of their career options. An indicator of how well the program is succeeding on this outcome could be the number and percent of participants who list more careers of interest to them at the end of the program than they did at the beginning of the program. A target might be that 40 percent of participants list at least two more careers after completing the program than they did when they started it.

Why Measure Performance Outcomes?

In growing numbers, service providers, governments, other funders, and the public are calling for clearer evidence that the resources they expend actually produce benefits for people. Consumers of services and volunteers who provide services want to know that programs to which they devote their time really make a difference. That is, they want better accountability for the use of resources. This, however, while relevant is not critical.

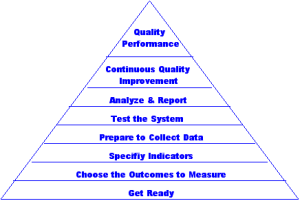

Although improved accountability has been a major force behind the move to outcome measurement, there is an even more important reason: to help programs improve services. Outcome measurement provides a learning loop that feeds information back into programs on how well they are doing. It offers findings they can use to adapt, improve, and become more effective. In this manner the organization can become a learning system with continuous quality improvement.

The initial question that needs to be addressed is “What is the purpose of the intervention?”. While the answer to that question may vary in noncrucial ways with each individual, the discussion about this purpose is critical? Is the purpose to diminish symptomology? To gain insight? Correct the problem? Protect society? Change the behavior? etc., etc., etc. Or is it to teach the client how to change what s/he wants to change?

One clear and compelling answer to the question of “Why measure outcomes?” is: To see if programs really make a substantive difference in the quality of the lives of people.

This dividend doesn’t take years to occur. It often starts appearing early in the process of setting up an outcome measurement system. However, as you approach quality, it becomes harder. Often you will need to be creative in determining what do I do now! The data indicates that what you are doing is not having the expected outcome, but you are limited in knowing what to try next. You have tried ‘everything’. Two approaches should be indicated. First, there should be an extensive search of the literature to identify effective approaches – the ‘cutting edge’, and next there should be a formalized process of creative thinking – using the tools to help staff, and perhaps clients, think through the issues.

Just the process of focusing on outcomes – on why the program is doing what it’s doing and how people think that participants will be better off – gives program managers and staff a clearer picture of the purpose of their efforts. That clarification alone frequently leads to more focused and productive service delivery.

Down the road, being able to demonstrate that their efforts are making a difference for people pays important dividends for programs. It can, for example, help programs:

- Recruit and retain talented staff: job satisfaction is difficult in human services. Too often our efforts seem in vain, our clients seem to ignore our pains, and the salary is not sufficient to make all of this worthwhile. When staff can see the trends of outcome expectations move in positive directions and are able to tie their own efforts to this movement – intrinsic reward prevails.

- Enlist and motivate able volunteers: other people will also observe this heightened esprit de corps – and see the learning opportunities.

- Attract new participants: clients will choose those services with a track record of effectiveness.

- Engage collaborators: other organizations will want to use the learning experiences in their own shops.

- Garner support for innovative efforts: it is certainly easier to get venture capital for an organization with a positive outcome track record.

- Win designation as a model or demonstration site: management staff become leaders in the field.

- Retain or increase funding: even though funding sources are not usually asking for this information, they will find it easier to defend grants or allocations by having it.

- Gain favorable public recognition: the general public is desperately seeking accountability to final cause.

Results of outcome measurement show not only where services are being effective for participants, but also where outcomes are not as expected. Program managers can use outcome data to:

- Strengthen existing services;

- Target effective services for expansion;

- Identify staff and volunteer training needs;

- Develop and justify budgets;

- Prepare long-range plans; and

- Focus board members’ attention on programmatic issues.

To increase its internal efficiency, a program needs to track its inputs and outputs.

To assess compliance with service delivery standards, a program needs to monitor activities and outputs.

But to improve its effectiveness in helping participants, to assure potential participants and funders that its programs produce results, and to show the general public that it produces benefits that merit support, a program needs to measure its outcomes.

These and other benefits of outcome measurement are not just theoretical. Scores of human service providers across the country attest to the difference it has made for their staff, their volunteers, their decision makers, their financial situation, their reputation, and, most important, for the public they serve. The rewards have been impressive enough to lead governments and private funders to pick up the idea. The 1993 Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA), for example, require federal programs to identify and measure their outcomes. Many foundations now require programs they fund to measure and report on outcomes.